© Good Travel Guide, August 2021

Author: Louise de Hemmer

Olympic medals made from recycled smartphones and laptops donated by the public, athletes sleeping on recycled cardboard beds, podiums made from recycled plastic, the torchbearer uniforms made from recycled Coca Cola bottles, a hydrogen fueled Olympic torch created with aluminium that comes from the construction waste of temporary housing built after the earthquake and tsunami of 2011… Does that mean that the Olympic Games are becoming “sustainable”?

While the Olympics can never be 100% sustainable, we examine why it’s worth looking at these claims in more detail.

Sustainability in the Olympic games

For the past decades, the International Olympic Committee has become more aware of the role that the Games could potentially play in nurturing economic, social and environmental sustainability. There has been extensive research that shows the positive economic and social impacts sport tourism and the presence of mega sport events, such as the Olympic Games, can have internationally and on host destinations (Lindsey, 2008; Hinch et al, 2016). However, research about the environmental impact of these sorts of events is very limited.

The Olympic Games do not have the best reputation when it comes to environmental sustainability and have very often been criticised for contributing to the creation of enormous facilities that are damaging the local environment and are quickly abandoned after the event. Following the environmental damages and major community backlash faced by the Albertville 1992 Winter Olympic Games,where the creation of infrastructures needed for the Albertville 1992 Winter Olympics led to significant alteration of the terrain, leading to increased chances of landslides, destruction of ecosystems through deforestation and natural animal habitats (Weiler and Mohan, 2010). From then on, sustainability became an increasingly important topic when considering the Olympic Games and for the International Olympic Committee, which included adding sustainability as a third pillar alongside sports and culture. Cities bidding for the 2002 Games were the first to be officially evaluated on their environmental plan during the bidding process. Since then, every city bidding to host the Games have included strong environmental sustainability promises. In 2008, UNEP signed an accord to help Beijing host the “greenest ever” Olympic Games. In 2012, London hosted the “Towards a One Planet Olympic” games. In 2016, Rio’s bid included hosting “Green Games for a Blue Planet”. Organisers of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games and of the 2024 Paris Olympic Games have pledged the Games will be net-zero carbon emissions.

“Be Better, together. For the planet and the people”

The sustainability concept of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games is “Be Better, together. For the planet and the people”, committing to zero carbon emissions, but also zero waste and much more as you can see below (Figure 1).

2020 Tokyo Olympic Games carbon offsetting system: pros and cons

Despite putting in place energy saving measures and using renewable energy, an event can never truly be net-zero carbon emissions. To work towards net zero, organisers have purchased carbon credits to offset their emissions. The Japanese Olympic Committee had pledged that the event’s carbon footprint would be no more than 2.73 million tonnes (the equivalent of a year’s energy consumption of 328,755 homes). With the absence of spectators, this number will be reduced, but with still 18 out of 43 venues being built specifically for the Games, the emissions linked to construction are still significant (Table 1). For more details on the carbon footprint calculations of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, read the Sustainability Pre-Game report.

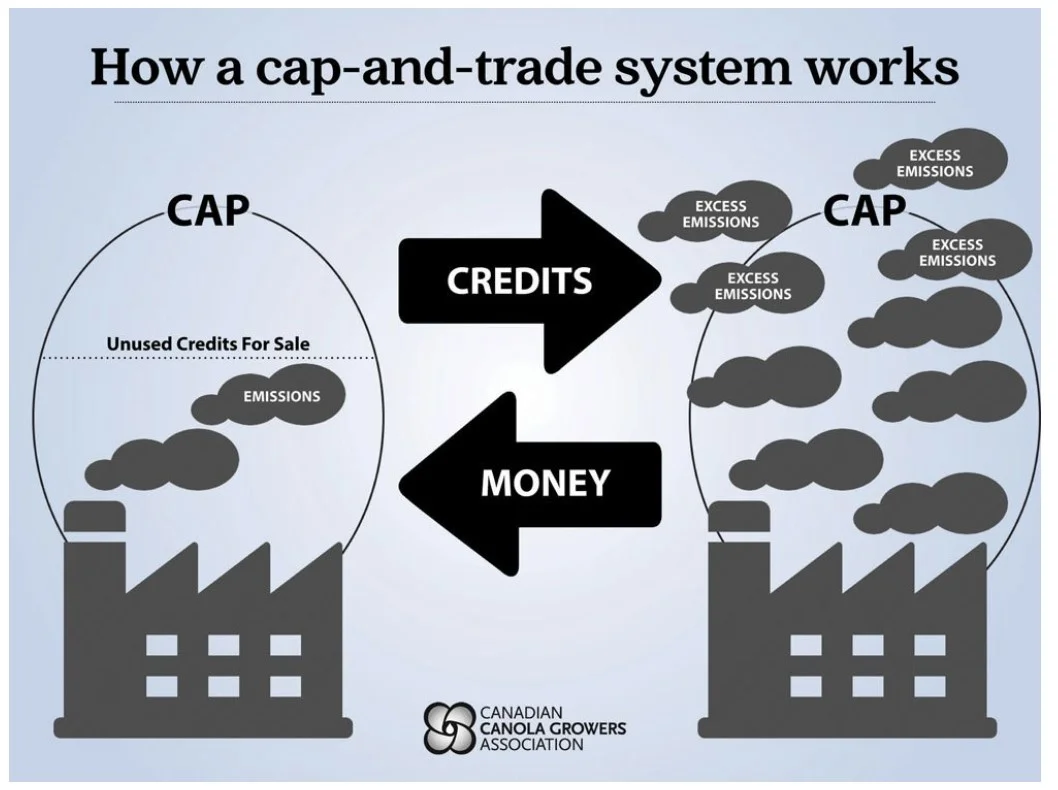

Even though the organisers of the event claim that their offsetting strategy is the best that Olympic Games have ever had, purchasing 4.38 million tonnes worth of carbon credits, this does not mean that the Games are sustainable. The issue with offsetting using a cap and trade system such as the ones that the Japanese Olympic Committee implemented (Figure 2), is that it will reduce carbon emissions in the future, but not stop emissions produced now, which therefore, still contribute heavily to the disruption of climate.

While it’s not the best system, it does however, still have some benefits to the environment that the Rio or Sochi Olympic Games did not have:

- By purchasing carbon credits from local businesses, they are incentivising them to reduce their carbon emissions (so they can use the carbon credits as investment or a new source of income).

- By working through carbon offsetting programs already in place in the country (through the Tokyo Metropolitan Government and Saitama Prefecture Government), they are able to reach a large number of local businesses.

- Focusing the offset program on local businesses could lead to long lasting change in the country.

Table 1: Carbon Footprint of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games

Figure 2: Cap and Trade carbon offsetting system

There is still a lot more that the International Olympic Committee could and should do in order to significantly reduce the impact of the mega events on the planet. There is a climate emergency and we cannot rely on offsetting systems with the hopes that the carbon emissions produced will be reduced in the future, they need to be significantly reduced now. Working towards a more circular economy of the Olympic Games, using facilities already available in the host destination and only creating new facilities when they benefit the local populations rather than just to accommodate huge numbers of visitors for a one-off event. Using existing facilities might contribute to limiting the number of visitors to the event, due to limited space in these facilities, and might also contribute to embedding the Olympic Games in residents’ daily life, making it more accessible for them and creating a relationship between locals and visitors.

The Paris 2024 Olympic Games committee is also claiming that they are putting sustainability at the heart of the project. Amongst other things, they have committed to using 95% of existing or temporary venues, limiting constructions to two new venues: the Olympic and Paralympic Village and the Aquatics Centre. According to the committee, these constructions have been embedded in local development plans to meet the long term needs of the local populations.

Will Paris set new standards for mega sport events in the future in terms of sustainability?

References

- Weiler, J. and Mohan, A., 2010. The Olympic Games and the triple bottom line of sustainability: Opportunities and challenges.

- Lindsey, I., 2008. Conceptualising sustainability in sports development. Leisure studies, 27(3), pp.279-294.

- Hinch, T.D., Higham, J.E. and Moyle, B.D., (2016). Sport tourism and sustainable

- destinations: foundations and pathways.